SEE THE RECORDING HERE:

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=LZ8zWwWJLLA&feature=youtu.be

The topics are: 1) Protesting, Rioting, Looting; and 2) the Militarization of the Police

The process will be as usual, two short video clips, each followed by discussion among the attendees, and a closing video clip.

Disclaimers : 1) The formal meeting will be recorded, 2) Media may be present and may use quotes from attendees on the air, 3) the language in the first video clip may be offensive to some people.

Attached are a few “think pieces” including the link to Vicki Brown’s oped in the Gazette on July 20, 2020.

Neil Deupree

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Obituary: John Lewis, US civil rights champion

“Hold only love, only peace in your heart, knowing that the battle of good to overcome evil is already won.

“Choose confrontation wisely, but when it is your time don’t be afraid to stand up, speak up, and speak out against injustice.”

John Lewis forged his legacy as a lifetime champion for civil rights and racial equality during the struggles of the 1960s as he preached a message of non-violence alongside Dr Martin Luther King Jr.

It was in March 1965 that Lewis, aged only 25, stood with other civil rights leaders as they led peaceful protesters across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. Their planned march would take them to Montgomery, the state capitol, to demand equal voting rights.

As they crossed the bridge, armed Alabama police officers on horseback carrying tear gas, whips and bully clubs attacked them. At least 40 protesters required treatment, and Lewis suffered a fractured skull.

Media outlets from across America captured the brutal attack on film, calling it Bloody Sunday. The event became a pivotal moment in the battle for civil rights for African-Americans, as Americans outside the South could now see the abuse inflicted upon the black community under “Jim Crow” segregation laws.

Five months later, with Lewis among the collection of civil rights leaders at the White House, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 into law.

Lewis was born on 21 February, 1940, during the time of Jim Crow laws, to a family of sharecroppers in the small Southern town of Troy, Alabama.

He was one of 10 children, and from an early age he expressed an obvious love of learning. Lewis would spend hours upon hours at his local library, and it was here where he could find African-American publications that would embolden his commitment to the struggle for civil rights.

“I loved going to the library,” said Lewis. “It was the first time I ever saw black newspapers and magazines like JET, Ebony, the Baltimore Afro-American, or the Chicago Defender. And I’ll never forget my librarian.”

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESAs a young black man growing up in the American South, the battle for racial equality actively shaped his life long before he became an activist. In 1954, when Lewis was only 13, the Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, ruled in favour of Brown vs Board of Education, striking down more than 50 years of legalised racial segregation.

Alabama, along with many other states, fought the decision and delayed implementation of school desegregation. Lewis’ school remained segregated despite Brown, and Alabama’s commitment to segregation forced him to leave the state to attend college.

Lewis aspired to attend the nearby, all-white Troy State University and study for the ministry, but the school’s segregationist stance meant it would never accept him.

In 1957, Lewis finally decided on attending the predominantly African-American institution, the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee, because it allowed students to work for the school in lieu of tuition. Yet during his first year in Nashville, as the fight against segregation continued, Lewis attempted to transfer to Troy State.

He sent in an application, but never heard back from the school. It was common during this time for segregationist schools to ignore the applications of African-Americans instead of formally accepting or denying them.

After growing frustrated by Troy State’s lack of response, Lewis wrote a letter to King describing his dilemma. King responded by sending Lewis a round-trip bus ticket to Montgomery so they could meet.

This meeting would commence Lewis’ relationship with King and his lifelong leadership in the struggle for civil rights.

Lewis eventually decided to end his dream of entering Troy State University after consulting King. Lewis’ parents had also feared their son would be killed, and their land taken away, if he continued to challenge Jim Crow laws. Instead, Lewis returned to Nashville, graduated from the seminary, and went on to earn a Bachelor of Arts in religion and philosophy.

Throughout college, Lewis remained an important figure in the civil rights movement, organising sit-ins at segregated lunch counters. In 1961 he became one of the 13 original Freedom Riders, seeking to end the practice of segregation on public transport.

At the time, several southern states had laws prohibiting African-Americans and white riders from sitting next to each other on public transportation or in bus terminals. The original 13 – seven white and six black – attempted to ride from Washington to New Orleans. In Virginia and North Carolina, the Freedom Riders evaded conflict, but all of that changed as they moved further south.

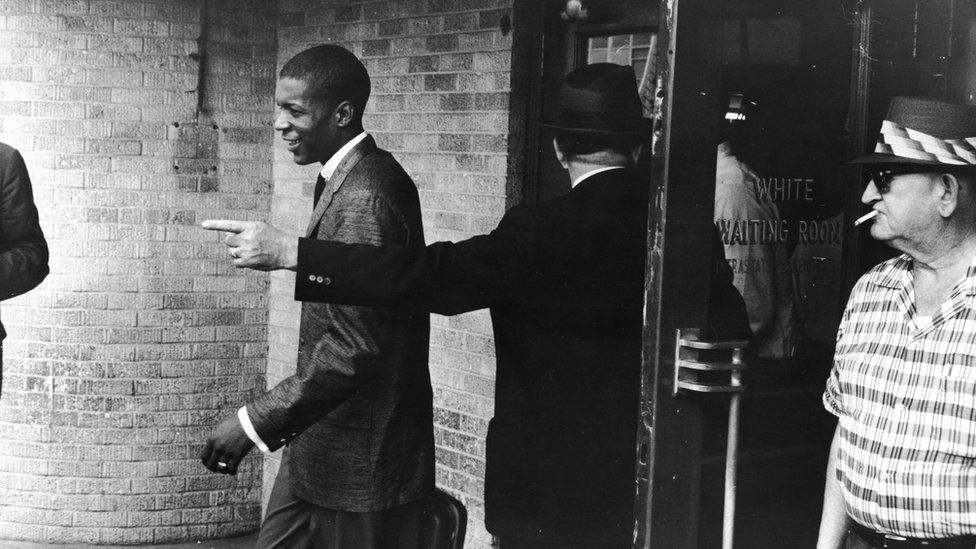

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESIn May 1961, Lewis was attacked by a mob of white men at a bus station in Rock Hill, South Carolina, for attempting to enter a waiting room marked “Whites”. Lewis was beaten and bloodied on that day, but his commitment remained undeterred.

In the Deep South, Lewis and other Freedom Riders were beaten by angry mobs, arrested, and jailed for sitting or standing next to white people on buses and in bus terminals. Some of the original riders left due to the violence and terror, but Lewis continued all the way to New Orleans.

In 2009, Lewis was reunited with his Rock Hill attacker, only this time instead of a clenched fist he was shown an open hand and a request for forgiveness. Elwin Wilson, a former Klansman who attacked Lewis, said that the election of President Barack Obama had spurred him to admitting his hateful acts and to ask for forgiveness from Lewis.

“I said if just one person comes forward and gets the hate out of their heart, it’s all worth it,” said Wilson. “I never dreamed that a man that I had assaulted, that he would ever be a congressman and that I’d ever see him again.

“He was very, very sincere, and I think it takes a lot of raw courage to be willing to come forward the way he did,” said Lewis. “I think it will lead to a great deal of healing.”

In 1963, when aged only 23, Lewis became the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), making him one of the “Big Six” civil rights leaders of the era. These leaders would organise the 1963 March on Washington, where King would give his historic “I Have A Dream” speech. Lewis, at an age when most people had just begun their professional careers, also stood atop the Lincoln Memorial and gave a rousing oration about the importance of fighting for civil rights.

“We are tired,” Lewis said in his speech. “We are tired of being beaten by policemen. We are tired of seeing our people locked up in jail over and over again. And then you holler, ‘Be patient’. How long can we be patient? We want our freedom and we want it now.”

Image copyrightBETTMANN/GETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightBETTMANN/GETTY IMAGESIn March 1965, Lewis, King and other civil rights leaders organised the march from Selma to Montgomery that became a tipping point in the battle for civil rights and the eventual passage of the 1965 Voting Rights amendment.

Throughout his early civil rights career, King remained Lewis’ mentor, the man Lewis said “was like a big brother to me”.

“[He] inspired me to get in trouble – what I call good trouble, necessary trouble,” Lewis later told the Washington Post. “And I’ve been getting in trouble ever since.”

Lewis was in Indianapolis in April 1968, campaigning with Democratic presidential candidate Bobby Kennedy, when Kennedy announced that King had been assassinated.

“It was such an unbelievable feeling,” Lewis said. “I cried. I just felt like something had died in all of us when we heard that Dr Martin Luther King Jr had been assassinated. But I said to myself, well, we still have Bobby. And a short time later, he was gone.”

After leaving the SNCC in 1966, Lewis remained active in civil rights in Atlanta, working on voter registration programmes and on helping people rise out of poverty.

When Jimmy Carter won the successful presidential bid, Lewis took a position with the federal domestic volunteer agency and in 1981, after Carter lost the White House to Republican Ronald Reagan, Lewis returned to Atlanta and was elected to the City Council.

Five years later he ran successfully for Georgia’s fifth congressional district, and held his seat until his passing.

To help acquaint a new generation of Americans with the fight for civil rights in the 1960s, Lewis co-created the three-part graphic novel March, a vivid memoir of his lifetime of civil rights advocacy that went on to be a bestseller and award-winner.

As a young activist, Lewis had himself been inspired by the 1958 comic book Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story. Through his own graphic novel, he hoped to inspire another generation of civil rights leaders.

“We are involved now in a serious revolution,” it says in March: Book Two, published in 2015. “This nation is still a place of cheap political leaders who build their careers on immoral compromises and ally themselves with open forms of political, economic and social exploitation.

“What political leader here can stand up and say, ‘My party is the party of principles?'”

In 2014, the film Selma depicted the events of Lewis’ historic march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and was released to wide acclaim. It further cemented Lewis’ legacy as a civil rights icon.

He recreated the journey across the bridge in March 2015, but this time with Barack Obama, America’s first black president.

“It is a rare honour in this life to follow one of your heroes, and John Lewis is one of my heroes,” Obama said at the 50th anniversary celebration.

Image copyrightAFP/GETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightAFP/GETTY IMAGESDuring Donald Trump’s presidency, Lewis fiercely opposed the policies and statements made by the president and his fellow Republicans. Lewis boycotted Trump’s inauguration, saying he did not believe he was a “legitimate president” because of Russian interference in the 2016 election.

He went on to repeat concerns about the direction he felt the US was taking in 2017, after the white supremacist rally and attack in Charlottesville, Virginia.

“I am very troubled,” he said. “I cannot believe in my heart what I am witnessing today in America. I wanted to think not only as an elected official, but as a human being that we had made more progress. It troubles me a great deal.”

Despite this Lewis remained an undeterred and committed champion for the fight for civil rights and racial equality until his last breath.

“When you see something that is not right, not fair, not just, you have to speak up. You have to say something; you have to do something” – John Lewis.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

George Yancy: To Be Black in the US Is to Have a Knee Against Your Neck Each Day

What drives the current rift between white and Black America, and how as individuals can we effectively contribute to the fight against the worldmaking of whiteness?

Philosopher George Yancy a leading public intellectual in the critical study of race who received backlash for pointing out the U.S.’s yoke of whiteness argues that white supremacy breathes at the site of Black asphyxiation.

In this exclusive Truthout interview, Yancy discusses the racialized dimensions of COVID-19 vulnerabilities, Donald Trump’s displays of white nationalist aspirations, the un-sutured pain of living as a Black person in the United States, and the much-required insurrection against white ontology itself.

Woojin Lim: A lot has changed since you published your series of interviews on The Stone and penned your provocative letter, “Dear White America,” in 2015. How have these changes impacted your views, and which parts of your column would you revise, if at all?

George Yancy: One might think that I would revise my view within the context of the recent massive protests that are both local to the U.S. and global. One might surmise that given the multiracial composition of the protests that I might change how I addressed white people in that letter. The protests, however, only reveal what I had in mind back in 2015: whiteness is the problem, not Blackness. Moreover, once we reach a “post-George Floyd” moment, those same whites who protested will continue to reap benefits from being white in a country that will continue to be based upon white supremacy. That is the recursive magic of white supremacy. It is able to accommodate or to consume what we throw at it. It is able to make a space for protests and even reform while precisely sustaining itself through the power of its consumptive logics. So, in retrospect, I would not change anything in terms of the argument delineated within “Dear White America.”

How do you understand “the more” that is necessary as the world bears witness to these protests within the U.S. and abroad?

Let me first acknowledge that the protests in the U.S. and abroad have ignited an important anti-racism awakening that has been long overdue but requires far more work. There have been some meaningful outcomes, such as confederate statues toppled, the ban of chokeholds, discussions and commitments regarding the defunding of police, school districts across the U.S. committing to removing police from schools, and millions of dollars have been donated to racial justice groups. However, we need to do more. We are not disrupting whiteness in ways that will fundamentally make a difference in terms of how it continues to operate through various white gazes, white forms of inhabiting space, white forms of maintaining “innocence,” white forms of deep structural power and normativity. What we need is an insurrection, as Judith Butler might say, at the level of white ontology itself.

I often return to James Baldwin’s powerful and passionate letter to his nephew where the former says that it is the innocence which constitutes the crime. Baldwin’s point is that the very process of attempting to secure one’s “white innocence” in the face of so much Black existential pain and suffering caused by white supremacy is a crime. The self-deception is criminal, or perhaps the effort itself is criminal. The history of white supremacy is there for all to see; North America’s 400 years of anti-Black racism reveals its mythical standing as a “beacon of hope”; American exceptionalism is, for Black people, a site of un-exceptionalism when it comes to its ideals of democracy vis-à-vis its reality as a white Herrenvolk or “master race” polity.

Baldwin also reminds us that those who shut their eyes to reality or those who insist upon their innocence long after it is gone only create monsters. Donald J. Trump is a monster. Just consider his neofascist tendencies, his racist comments, his unabashed white nationalist aspirations, his attempts at demonizing the press, his draconian desires to silence dissent. Henry Giroux is right to call out Trump for both his “pedagogies of repression” and his “dis-imagination machine.” Keep in mind that in 2017, Trump stated that there were “very fine people on both sides” in Charlottesville, Virginia. The other side to which he was referring consisted of neo-Nazis, the “alt-right” and white supremacists. This is the same man who degradingly referred to a number of African nations as “shithole countries.”

Or, more recently, think of Trump’s comment regarding Detroit, Baltimore and Oakland, which I take to be majority-minority cities: “These cities, it’s like living in hell.” Being Black in North America is like living in hell, but for reasons Trump either doesn’t know, refuses to know, or knows and doesn’t give a damn. Being Black in America is to be in a living hell. If you don’t believe this, then resurrect those Black bodies lynched, castrated, raped and beaten during slavery and after. That hell of anti-Black racism began much earlier. Resurrect the millions of Black bodies that died during the Middle Passage bodies that could not breathe in the holds of slave ships where their bodies commingled with blood, vomit, feces, urine, disease and the stench of death. You see, not being able to breathe didn’t begin with Eric Garner or George Floyd. It began in the Middle Passage. As Black people, we are still in the middle of that passage — suffocating, dying, ontologically frozen by the trauma of a white gaze that doesn’t truly give a damn about Black life. It will take much more than whites protesting in the streets to grapple with that problem, especially as our failure at breathing is based upon white people’s success at breathing.

I now clearly understand that Trump is the expression of a larger id of white supremacy. He is the manifestation of an unchecked domain of white racist violence, myths of white superiority, myths of white manifest destiny. But we need to keep in mind that his election wasn’t the inaugural event that created what we are seeing in such blatant forms. He is a product of that. His election is the manifestation of a species of retaliation for any “Black progress.” The assumption at work here is one of white zero-sum logics: Black gain is deemed white loss, which, of course, is based upon white fear and a challenge to white privilege and white ownership of power. So, I would not change anything in “Dear White America.” I would remain true to its primary message, and I would do so with love: whiteness is a systemic structure and thereby to be white belies any sense of white innocence. In fact, I would argue that “Dear White America” functioned as an attempt to sting the conscience and consciousness of white people; it was a clarion call against forms of white perceived innocence.

To play on words with your 2018 book, Backlash: What Happens When We Talk Honestly about Racism in America, what exactly happens when we talk honestly about the lived experience of racism today? What does it mean to be Black in America?

In that title, the lived experience of racism had to do with the lived experience of racism that I encountered after writing “Dear White America.” That experience was one of white terror, threats of physical violence, death threats, perverse projections from a deep-seated white libidinal desire in relationship to the Black body (my Black body), racist epithets, and the deployment of “nigger.” That term continues to carry the weight of a punch in the face, a kick in the back; it remains assaultive. Again, pointing to Baldwin, white people really do need to ask themselves why they needed to create that term (“nigger”) in the first place. By asking such a question, perhaps they will come to realize that what is necessary is that they address ways in which they have split themselves off from aspects of their own hated selves. After all, Black people did not create that term.

Thinking about the full title of that book, I would say that there is much to pay for those who refuse to tip-toe around the question of white racism, white power and white privilege. For me, that honesty and courage is not something that Black people or people of color must carry alone. White people must be prepared to talk honestly about racism in the United States, but to do so requires a certain symbolic death, where one encourages the death of the semiotics of whiteness, its oppressive material reality, where one is prepared to self-empty, to refuse the price of the ticket to “become white” and thereby anti-Black.

Another way of thinking about the lived experience of racism is to talk about the horrors of whiteness as they are experienced within the context of the mundane, the everyday. This point is so incredibly important at this moment in U.S. history. The death of George Floyd is what I would call a spectacular form of white racism on display. The emphasis is on the term “spectacular,” which etymologically suggests that which is clearly seen, indicative of a show. And while we know that the brutal and slow murder of George Floyd had nothing to do with theatrics, my point is that Black people experience forms of quotidian white racism all the time, where these forms of racism are not caught on video. Let’s call this the banality of whiteness.

Think about what it means to be Black at predominantly white universities and college campuses, which are the spaces within which I have taught for nearly 20 years. It means to undergo forms of deep racial alienation. Some Black students and students of color have to cope with white people, believe it or not, who have never interacted with people who are not white. This points to the existence of de facto racial segregation. So, out of these white spaces grow distorted racist desires and assumptions: “Can I touch your hair?” “You are very articulate.” “You don’t sound Black.” “Tell us what it is like to witness a murder?” “What sport do you play?” “Where are you from, really?” “But I don’t hear your accent.” “You speak English so well.” “You are so angry.” “Stop being so sensitive.” “But you’ve made it. Why complain?” These moments are not spectacular, but that does not mean that they are less racist or any less painful for those who feel like targets. Imagine the sense of finding it hard to breathe, hard to move within those spaces with ease or with effortless grace, imagine the impact on trying to study, imagine what it’s like to take a stroll across campus after a week or even a day of such microaggressions. These interactions function as acts of micro-violence. They are nonspectacular moments of deep pain, hurt and sorrow, but still forms of racial cruelty predicated upon larger systemic necropolitical violence where state power shapes who lives or who dies, unevenly, through a racial and racist framework.

So, for you, what does it mean to be Black in America?

It means to be subjected to forms of white systemic violence everyday of one’s life. To be Black in America is to grieve one’s own death that is always already imminent or looming within a country that was founded upon a system of beliefs and practices that said that you are not human. To be Black in America means to be murdered by the white state and white proxies of the state. It means walking through a gated community minding your own business and being shot dead (Travon Martin), shot in the back and killed while fleeing (Walter Scott and Rayshard Brooks), shot and skilled while in the “safety” of one’s own home (Botham Jean, Atatiana Jefferson, Breonna Taylor), shot while out jogging (Ahmaud Arbery), arrested while innocently sitting in a Starbucks (Rashon Nelson and Donte Robinson), threatened through the weaponization of white womanhood as you ask a white woman to leash her dog (Christian Cooper). I have come to embrace a formulation, which I’m sure has its origin in Afro-pessimist theorizing, that says that the opposite of Blackness is not whiteness, but the human. In short, to be Black is to fall within the category of the “sub-person,” the “subhuman” or perhaps even the “unhuman.” To be Black in America is to deal constantly with white macro scenes of Black death and dying, Black disrespect, Black nullification, Black ontological truncation, Black epistemic injustice, Black degradation, Black policing, Black confinement, Black precarity, Black fatigue, Black inequality, Black poverty, Black hunger and systemic Black marginalization. In short, to be Black in America is to have a knee pressed against your neck and to die just a little each day; it is a form of gradual asphyxiation that is your birthright.

As a target of white racist vitriol and death threats, what were your coping mechanisms, the guiding light that you clung to?

That one is easy. I have Black children and I want them to live. The threats will come, they will continue. And while Black people cannot be the “saviors” of white people, I must attempt, with all of my strength, to protect my Black children. This is not some abstract ethical commitment but a daily and concrete loving effort that understands their reality and that recognizes their racial precarity. As a Black parent, I feel it each day when a child of mine walks out into the world, into the toxicity of anti-Black racism. You see, they don’t need to do anything that will result in their not coming home ever again. All that is necessary is that they are Black in a white supremacist United States. What keeps me stable is that love for them. So, I must write that next essay, write that next book and give that next lecture that reveals the truth about a white Untied States. What also grounds me, though my pessimist tendencies seem to be winning out, is the belief in an open future. After all, I don’t believe that whiteness has a metaphysical monopoly on the future. Yet, there is nothing about the past or the present that says, without question, that anti-Black racism will ever completely come to an end. So, the guiding light is to save the lives of my Black children, to have them return home, not to get that call to come down to the morgue to identify the lifeless body of my Black child who has been killed because some white police officer said that they “felt threatened.”

What is “white America” to you?

For me, “white America” is a structural lie. And by this, I mean that it was/is predicated upon abstract ideals that it never intended to apply to Black people or people of color. And even where there is “progress” for those of us whose lives don’t matter, it is important to recognize that such alleged progress occurs within the framework of white interests. The critical race theorist Derrick Bell made this clear with his theory of interest convergence, which shows that racial justice for Black people only happens when white and Black interests converge. So, the implication is that Black progress is tolerated as long as it doesn’t fundamentally challenge white interests. This still prioritizes whiteness.

This further speaks to the ethical vacuity of white America as a structure, as a system that consists of white people who consciously or unconsciously invest in whiteness. Returning to what I’ve said earlier, this means that “white America” attempts to obfuscate its practice of anti-Black violence through forms of distorted white self-narration. The lies are familiar: the majority of whites are innocent of racism; racism is an aberration enacted by a few bad whites; the U.S. doesn’t see color; we are clearly a post-racial country because otherwise how could we have elected the first African American president.

This is why we need to be critically aware at this moment and nurture a critical imagination. Many whites are protesting, shouting that Black lives matter. I get it. But Malcolm X was right. If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches that is not progress. He goes on to say that even if the knife is pulled out all the way, there is still no progress because progress is healing the wound that was originally made. And like Malcom, I don’t see the U.S. willing to remove the knife or willing to heal the wound. It feels as if salt is being poured on that open wound every day. The protests that we are witnessing will not heal the wound. And while it is important that white people protest the killing of Black bodies and racist policing, it is also important to think about how white protestation can function as a form of virtue signaling — you see, we are good whites. I don’t want white people to build monuments of white virtue on my back as I’m lying in the street dead because some white police officer could not, as Claudia Rankine says, police his or her own imagination.

How would you define the project of “undoing whiteness”? How can white Americans confront the ways in which they benefit from racism?

Undoing whiteness will certainly not happen by simply understanding that whiteness is a site of fragility. That term does some work, but it is very misleading. It often suggests that white people are these delicate creatures who would understand their racism, but only if they realize that they are operating from a defensive place of fragility. That is too consoling. White people must be prepared to accept the lie that is their whiteness. It’s not about fragility. It’s about white people’s desire to maintain their white power, white privilege and white innocence. History has given them the blinkers, the shelters to use to protect them from facing the lie and violence of whiteness, their whiteness.

I am often asked if there is an easier way to explain to white people the meaning of their whiteness without raising the issue of their racism. I think that posing such a question presupposes white fragility. If Black people must face the fact that their existence doesn’t matter within a white racist United States, then white people must face the truth that their existence is secured, protected and rendered “sacred” because Black existence isn’t. That means that white people are complicit with George Floyd’s death. It is not simply about Derek Chauvin. It is the fact that to be white in the United States involves, as Joel Olson would argue, never having to occupy the position of Black people, because that place is always taken.

What is needed is a form of kenosis or self-emptying. This is a process where white people die a symbolic death, a death that has deep affective, epistemological, ethical and metaphysical implications. It means ending the world of whiteness, not white people. What comes after the death of whiteness may very well produce a form of humanity that has been held captive by whiteness. Yet, this will also require removing white masks, unveiling the systemic oppressive forms of whiteness, asking white people to be vulnerable, to tarry with forms of being un-sutured, and having their souls laid bare.

If whiteness is nothing other than oppressive and false, as David Roediger has argued, why cling to it? Back to Baldwin: “Any real change implies the breakup of the world as one has always known it, the loss of all that gave one an identity, the end of safety.” That is what is necessary in order to undo whiteness, the crumbling of white worldmaking, undermining all of the fictions that reinforce white identity, and a daring act of love — not the sentimental kind — that expresses itself through the risk of looking into that disagreeable mirror called Black critique, which is predicated upon deep forms of Black pain and suffering. Unlike Odysseus, white people must be prepared to take the leap, to risk all in the name of freedom from the idolatry of whiteness.

Should Black Americans be required to bear the weight of public witnessing in a world that displays “ethical cowardice and indifference,” and if not, whom else? How should responsibility be apportioned to Black and white people when attempting to overcome racial gridlocks?

I think that within a context of pervasive anti-Black racism, one has an ethical responsibility as a racialized Black person to bear the weight of speaking courageous speech against white racism. We can’t simply assume that white people will do this work through moral suasion. After all, history proves that. And even if they do it, we have to be careful that they are not doing so because of white noblesse oblige, or because of some deeply problematic reason to be a “white hero.” Those acts are perfunctory and re-center whiteness.

So, we need white people to do the work that is necessary to critically work through whiteness such that they are not reinscribing that whiteness. Unfortunately, so many white people are ethically cowardly and indifferent. The idea of losing their safety must be emphasized. In this way, they understand the magnitude of their responsibility. We can help them develop what I refer to as a form of white double consciousness, where they see themselves through the eyes of Black people. Yet, they must do the lion’s share of the work when it comes to what you’ve called racial gridlocks. Think about what is otherwise being asked of Black people. We have to deal with white racism and then teach white people about themselves. I recall being asked by a white woman philosopher once: “What do you want from white people?” Reflecting back on that question, I’m convinced that it functioned to privilege whiteness even as it gave the appearance of something “progressive.”

First, I shouldn’t have to ask white people for anything. They should (even if they don’t) see what is needed. Second, what made that white woman think that she could even provide what I needed? So, there was white arrogance. Third, structurally, her power was instantiated precisely in posing the question to me. Black people want to live, and we want to do so with our freedom and dignity intact. It is not only white people who must do the work, though. It is anti-Black racism that we are fighting against. And while whiteness is the fulcrum around which anti-Blackness moves, all non-Black people in white supremacist United States must also do the necessary work, especially if they are not Black, which, as mentioned, is a place already taken. So, there is a larger racial binary that must be interrogated, one for which whiteness is also responsible: not just Blackness and whiteness, but Blackness and non-Blackness.

I think that it’s important to see how such interracial minority conflicts between — for example, Asian Americans and African Americans — are fueled by whiteness just as intra-racial conflicts are fueled by whiteness. In the former case, think about the unnecessary tension caused by the model minority myth. In the latter case think about the toxicity of colorism within Black spaces. Both are generated within the logics of whiteness.

If there is one thing you would like the public to take away from your work today, what is your message?

I’m not sure if there is one thing. To answer your question, though, I’ll respond within the context of the gravity of our current reality. As I was thinking recently about the social and ethical challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, I began to feel and to articulate what I was witnessing. What we are witnessing is the collapse of the taken-for-granted, the normative structure of everyday life. And yet, for Black people, we continue to experience more of the same, more of the same disproportionate vulnerabilities, resource depletions, food deserts and massive inequities across various indices. COVID-19 is helping to unveil these realities, but “white America” has a short memory. Black bodies are piling up. This is and has been our history. Notice the connecting themes of death and dying, and not being able to breathe without struggling to do so. Despite COVID-19, Black bodies are still close enough to stop and to harass disproportionately, to murder unarmed and to publicly lynch.

This moment reminds me of 9/11 and the horrible events that took place at Abu Ghraib prison. Regarding the latter, then-President Bush announced, “This is not the America I know.” Yet, this is the America known by Black people. The xenophobic paranoia, sexual violence, sadistic brutality, we know that history. And 9/11 wasn’t the first terror attack on American soil. Black people have known white terror throughout the history of this country. So, what should be taken away from my work is the importance placed on white people to face the differential horrors that Black people face, and not to turn away and claim “innocence.”

For me, philosophy is a site of suffering. I ask questions about our inexplicable presence in this remarkably complex and apparently indifferent and silent universe, I bear witness to what Walter Benjamin calls “human wreckage,” and I am often the target of white racist vitriol. So, for me doing philosophy, wrestling with truth, is inextricably linked to pathos. Like Theodor Adorno and Cornel West, I believe that we must let suffering speak. I also ask that white people learn how to suffer along with, and take responsibility for, the social and historical wreckage that Black people experience because of anti-Black racism that exists here in the U.S. and abroad. And for those white people who say that they do suffer in this way, then I would ask that they show me their scars, allow me to place my hand in the wound that they’ve endured fighting against Black degradation, and fighting against the insidious structure of whiteness — their whiteness. I want white people to know that they are not pre-social, neoliberal subjects, that we are always already entangled in the lives of others and that they are especially entangled in the lives of Black people. Because of this, there is no “white innocence.”

Unlike Athena, who was born fully whole from the head of Zeus, we are born from the messiness and beauty of interlocking, collective human flesh — fragile, precarious. To echo Baldwin, I want white people to know that “everything white Americans think they believe in must now be reexamined.” If not for themselves, then for the love of their white children. Indeed, returning to your question about the guiding light that I clung to, I would also add deep love for the souls of white children. If their own white parents fail them, if white society fails them, what do they have? Who will help them not to flee reality? Who will help them to remove the masks, as Baldwin would say, that they will someday come to fear they cannot live without?

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

James Baldwin Was Right All Along

By Raoul Peck, The Atlantic

08 July 20

The writer and activist has the painful, powerful words for this political moment. America just needs to heed them.

“There are days—this is one of them—when you wonder what your role is in this country and what your future is in it. How, precisely, are you going to reconcile yourself to your situation here and how you are going to communicate to the vast, heedless, unthinking, cruel white majority that you are here. I’m terrified at the moral apathy, the death of the heart, which is happening in my country. These people have deluded themselves for so long that they really don’t think I’m human. And I base this on their conduct, not on what they say. And this means that they have become in themselves moral monsters.”

James Baldwin made this somber observation more than 50 years ago. I included these words in my film I Am Not Your Negro, which explored Baldwin’s searing assessment of American society through the lens of the assassination of three of his friends: Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X. It is a film that cruelly shortens time and space between acts of police brutality in Birmingham in 1963 and images of the 2014 protests in Ferguson, Missouri, after the killing of Michael Brown; recent images of protests over the death of George Floyd extend that tragic connection to the present-day.

It took me 10 years to make this film, but Baldwin put his whole life and body weight into these words, which, today more than ever, reverberate like a never-ending nightmare. With them, Baldwin dissected a story whose roots are deep. He exposed the underlying causes of violence in this country, and he would have continued to do so, year after year, one uprising after another, were he still alive today. And we still don’t get it.

Today, as protests against police brutality and institutional racism continue around the country, it is impossible to hide the scars anymore, the ugly facts, the videos, the overwhelming and systemic negation of human life. We can’t breathe! cried all the Black men who have been killed. If they can’t breathe, none of us should breathe, Black or white. These are the terms of the social contract. “It comes as a great shock to discover the country which is your birthplace and to which you owe your life and your identity has not, in its whole system of reality, evolved any place for you,” Baldwin said.

When I Am Not Your Negro came out, I was stunned that it did not cause riots or provoke my banning from the public for being the messenger of such cutting words. The film is based on Baldwin’s 30 pages of notes for a book project called Remember This House, which he ultimately never wrote, because it was too excruciating to do so. In it, Baldwin expressed profound truths about America that had never been said in such a direct and explicit manner:

I have always been struck, in America, by an emotional poverty so bottomless, and a terror of human life, of human touch, so deep, that virtually no American appears able to achieve any viable, organic connection between his public stance and his private life. …

This failure of the private life has always had the most devastating effect on American public conduct, and on black-white relations. If Americans were not so terrified of their private selves, they would never have become so dependent on what they call “the Negro problem.”

Baldwin’s words are forceful and radical; he punctures the fantasy of white innocence and an infantile attitude toward reality. He understood that there is extraordinary capacity for denial in this country, even when confronted with evidence and logic. His was a deep knowledge of the white psyche, which he thought was marred with immaturity. In this, he unsparingly exposed America’s original sins. First, the genocide of Native Americans: “We’ve made a legend of a massacre,” he said, which is a narrative “designed to reassure us that no crime was committed” and propagated by Hollywood’s “cowboys and Indians” stories. Then, the haunting legacy of slavery: As he said in a famous 1968 interview on The Dick Cavett Show, “I can’t say it’s a Christian nation, that your brothers will never do that to you, because the record is too long and too bloody. That’s all we have done. All your buried corpses now begin to speak.”

Denial of these sins, he made clear, is a powerful regulatory societal force, as mirrored, for example, in the entertainment industry. He wrote: “The industry is compelled, given the way it is built, to present to the American people a self-perpetuating fantasy of American life. Their concept of entertainment is difficult to distinguish from the use of narcotics. To watch the TV screen for any length of time is to learn some really frightening things about the American sense of reality. We are cruelly trapped between what we would like to be and what we actually are.” Other institutions have similarly erased history.

Why can’t we understand, as Baldwin did and demonstrated throughout his life, that racism is not a sickness, nor a virus, but rather the ugly child of an economic system that produces inequalities and injustice? The history of racism is parallel to the history of capitalism. The law of the market, the battle for profit, the imbalance of power between those who have all and those who have nothing are part of the foundation of this macabre play. He spoke about this not-so-hidden infrastructure again and again: “What one does realize is that when you try to stand up and look the world in the face like you had a right to be here, you have attacked the entire power structure of the Western world.” And more pointedly: “I attest to this: The world is not white; it never was white, cannot be white. White is a metaphor for power, and that is simply a way of describing Chase Manhattan Bank.”

Today, major corporations and leading institutions of entertainment, sports, finance, the press, and academia seem to have discovered for the first time not only how wrong they have been, but also how blind, stubborn, and insensitive. When will Wall Street and the sacred stock market question their role in this? Any serious conversation about systemic racism would have to start there too—maybe even primarily so. And artificial fixes will not do. A complete turnabout is required; a total reframing of rules and practices must take place, and substantial allocation of resources must come with it. The sociologist Kenneth T. Andrews wrote in 2017 about the need to “capitalize on the energy and urgency of the moment … and look to build a movement that generates new sources of cultural, disruptive and organizational power.” Today, a younger generation is in the streets. As Baldwin reminds us, we forget how young the actors of his time were.

The playwright Lorraine Hansberry was 33 years old when she attended a now-famous meeting in May 1963 between then–Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy and a group of artists and activists. Baldwin had arranged the gathering in hopes of inciting the president, the attorney general’s brother, to engage in a meaningful, symbolic gesture: escorting a Black student who was scheduled to enter a toxic, segregated school in the South. Stupefied by Bobby Kennedy’s dubiousness, Hansberry charged: “I am very worried about the state of the civilization which produced that photograph of the white cop standing on that Negro woman’s neck in Birmingham.” And then she left the room. She died a year and a half later.

If any lesson can be drawn from this meeting, it is that we’ve always known that people were subjugated, even murdered in such a way. Men, women, children. None of that is new. And this has been known at the highest level of this country.

And when Baldwin rhetorically asked himself almost 60 years ago, “What can we do?,” his answer was devastating: “Well, I am tired … I don’t know how it will come about, but I know that no matter how it comes about, it will be bloody; it will be hard.”

Baldwin has been right this whole time. There is nothing to add or to subtract. It’s up to you now to act upon it.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

by Vicki Brown

“This is a year like no other.

We just celebrated another holiday under a pandemic, with all of the restrictions, not being able to do what we want, go where we want, eat where we want, recreate where we want. Schools, libraries, beaches, swimming pools, movie theaters, and public gatherings are closed to us. The pandemic won’t let us live the way we want to live. Many can’t wait for things to get back to “normal”.

Some of us are learning about the restrictions of a pandemic for the first time. Yet communities of color have been living with the pandemic of racism for decades, centuries actually, being restricted daily on where and how to live, where and how to travel, where and how to gather, just to survive.

Our country cannot afford to go back to “normal.” We whites need to learn about the history of our country not told in the history books. Native American history is part of U.S. history. So, too, is the history of African Americans, Latinx Americans, Chinese Americans, and all Americans. U.S. history is more than just European American history.

It is time to educate ourselves on our collective history.

The Fourth of July is a celebration of the birth of the United States, when our founding fathers declared:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Yet, it would be nearly two centuries later that some Americans could actually hope for those words to be true.

Janesville Access Television periodically shows a keynote address by Dr. Jacqueline Battalora from the 2019 YWCA Rock County Racial Justice Conference, entitled “Going Back to Go Forward”, which I encourage you to watch. The former Chicago police officer explains how whiteness is baked into the DNA of our country. One of the keynotes for this year’s upcoming racial justice conference is author James Loewen, who will present on American history not shared in textbooks as well as on sundown towns.

Recent current events have started the education process for many white Americans on our shared past. Juneteenth, (June 19, 1865) also called Freedom Day, Jubilee Day and Liberation Day, has been celebrated for over 150 years by African Americans. It was the day the last slaves held in bondage were freed in Texas, a full two and a half years after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

Join the YWCA and the Elite Ladies of Beloit in June 2021 for our local Juneteenth celebration.

You have now heard of the events in Tulsa in 1921, whites destroying black Wall Street, at that time the wealthiest black community in the U.S. Yet Tulsa was not an isolated incident concerning the destruction of black-owned property. Inform yourself about Memphis 1892; Springfield, Illinois, 1908; Chicago 1919. The list continues.

Polls say the majority of Americans support Black Lives Matter. Are you aware there is no national hierarchy for this organization? It is member led at the local level. Want to learn more about BLM? Join us Aug. 20 as the Diversity Action Team and YWCA Rock County host a program on Black Lives Matter.

As we come out from the COVID-19 pandemic, there are hopeful signs that we may be stepping out from the racism pandemic. The NFL announced that before the football games the first week of the season the black national anthem will be played. Did you know there was a black national anthem? “Lift Every Voice and Sing” has been sung for well over 100 years! It was first performed in 1900 by segregated school children in Florida in honor of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday. I challenge you to learn the words prior to the start of the NFL season and sing along.

It is past time to educate ourselves on our collective shared American history. The information is readily accessible, including local programs right here in Rock County.

Bear in mind, when you know better, you need to do better.”